The Virgin Mary, who stands eight feet tall and weighs 1,000 pounds, presides over all who enter the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles. This Virgin Mary deviates from the typical braided hair, plain attire, and bare head and arms, as were the methods employed to build the statue.

Sculptor Robert Graham produced the Virgin Mary and the Cathedral doors, which stand 20 feet tall and weigh a combined 25 tons. Graham’s L-shaped outer doors frame cast-bronze inner doors representing the Virgin Mary in various incarnations. A tympanum – a gilded architectural element on which the statue rests – sits atop the doors.

Graham is known for his large-scale works, such as the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Gateway and sculptures of American heroes Joe Louis, Duke Ellington, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He began with a 30-inch sculpture of the Virgin Mary composed of plasticine, an oil- and wax-based clay that keeps detail but does not firm. The statue’s attire was then designed using a mold and polyurethane cast he manufactured. The Archdiocese of Los Angeles authorized this version; therefore, it was taken to Scansite in Woodacre, CA, to be 3D scanned and digitized.

Maintaining Detail at Large Scale (The Virgin Mary)

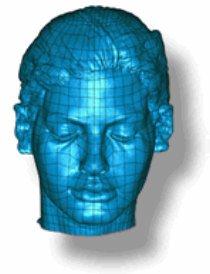

The polyurethane cast was coated gray before scanning to provide a level, even observe. Engineers scanned the head of the statue with a Cyberware MM laser scanner, the rest of the body was inspected by Cyberware MS3030.

“We broke the figure into parts for detailed scans of the head, body, arms, hands, and feet once the point cloud data were obtained from several scans of the complete piece,” says Noriko Fujinami, director of Robert Graham Studios.

Scansite combined data from each scan with varied resolutions to generate a highly detailed point cloud model of the whole figure. More than 1.7 million points were included in the final file.

The point-cloud data was sorted and entered into 3D Systems’ Geomagic Wrap program. Geomagic Wrap is used for 3D reverse engineering, taking a physical thing and automatically turning it into a digital model for design, engineering, mass customization, and web-based marketing applications.

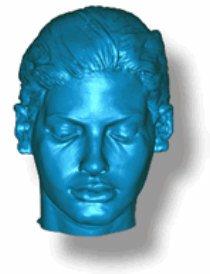

In Geomagic Wrap, Scansite developed a polygonal file of the statue. Engineers also used Geomagic Wrap at Ctek, a service bureau in Tustin, CA, to extend the figure from its original 30-inch size to its final 8-foot height.

“When you enhance surface data in a polygonal file, you enlarge the facets as well,” says Ctek executive vice president Javier Valdivieso. “We can utilize Geomagic’s subdivision tool to modify the surface and maintain its tangent at any scale.”

The engineers were also able to produce a water-tight surface using Geomagic Wrap, which allowed them to calculate the volume of the finished piece. Valdivieso and his colleagues were able to use this volume to create an interior armature that could hold the weight of the final bronze piece.

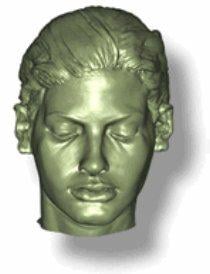

The resulting surfaces were fed into milling machines at Ctek’s headquarters, where the full-scale figure was machined in four pieces from clay. According to Fujinami, because of shrinkage caused by the bronze casting process, each part was machined three percent larger than required. After milling, the pieces were taken to Graham’s studio, where he resurfaced them by hand.

“The only software we found that could effectively duplicate the organic contours from the original sculpture was Geomagic Wrap,” Valdivieso explains. “Mr. Graham’s sculptures are highly detailed, with muscles, hair, and wrinkles. We wanted to make sure those things would work on a grander scale.

Without the trappings, Majestic

Engineers created silicone rubber molds once the final clay pieces were done. Graham utilized silicone molds to make the bronze statue, which was then cast using the lost wax method. “Wax was poured into the molds, which were then dipped in the ceramic shell to make a sturdy mold around the wax,” Fujinami explains. “Engineers melted wax out of the ceramic, and the mold was filled with molten bronze, resulting in a near-perfect duplicate of the original sculpture.”

The bronze components were welded together, and the final figure was sandblasted and silver nitrate patinated.

The final statue was brought from Robert Graham’s studio and assembled with the doors at the Cathedral site. Cardinal Roger M. Mahony, the archbishop of Los Angeles, dedicated the Cathedral on September 2, 2002. Graham’s vision demanded a high level of precision and nuance, which could only be achieved with the help of technology.

“The challenge I set was to make her majestic while dispensing with all the usual trapping and signals of majesty,” says Graham. “No crown, no scepter, no throne, etc., only her regal beauty, her invincible self-possession, and the abstract perfection of her gowns, like an apparition in its wrinkle-free smoothness and impossible triangle symmetry.”